When you’re standing at an intersection looking to cross the street, how many times do you press the walk signal call button? Do you press it repeatedly, or is once enough?

Unless you’re in a position to know the truth of the matter — say, you helped to design and implement the signal call — your answer depends on your beliefs about how it works.

Multi-pressers operate on the assumption that presses accumulate, signaling stronger volume of demand. Thus, the signal is more likely to change or even to do so sooner. Single-pressers believe that the system either has a request to change the signal or it doesn’t, so another press during the same traffic cycle won’t add any benefit.

The walk signal, like many of the systems we use each day, doesn’t lay out how it works to any satisfying level of detail. In the absence of information, these emerging beliefs are called mental models.

Let’s take a closer look at what mental models are and ways you can measure them in your user research.

What are mental models?

As a child of the ‘90s playing video games on consoles like the Super Nintendo and Genesis, one common issue you’d encounter was glitchy screens when you turned it on. Many of us would take the cartridge out and blow on the contacts to clear the dust. Unfortunately, we later found out that this could add moisture and do more harm than good. As it turns out, all you needed to do was simply remove and reinsert the cartridge to realign the contacts.

This anecdote highlights two key qualities of mental models.

First, they’re

beliefs about how something works, which may not always be factual or complete, and may even be entirely wrong. Accuracy isn’t always necessary, particularly in complex B2B settings where users don’t need full insight into back-end processes. What matters is that the mental model is accurate enough to empower users to achieve their goals, even if it’s only analogous or informationally equivalent to reality.

Second, mental models change how we interpret system feedback, and thus affect our decision-making and later behavior. So understanding and aligning the system with users’ mental models can have an outsized impact on the user experience.

While no two users have identical models, there are often similarities or themes observed within a user base. Going back to our example of the walk signal, we might broadly classify users into single-pressers or multi-pressers — but a closer inspection would show nuances, with individuals having varying levels of detail and formality in their mental models. Nevertheless, identifying common or representative models within a user base can help inform design changes.

Mental models are also adaptable and change based on experience.

An influential human factors study led by Roger Schvaneveldt that examined fighter pilots revealed distinct mental model structures between novices and experts. Novices had more diverse models, while experts held more similar models.

This flexibility presents an upside: with training or intuitive system design, users’ mental models can refine and become more accurate over time. For instance,

the market success of the Nest thermostat can be partly attributed to its interface aligning closely with users’ mental models, unlike traditional competitors. This underscores the potential impact of considering mental models in system design.

Approaches for measuring and analyzing them

There’s a wide range of methods for assessing users’ mental models, each with its own set of advantages.

The

think-aloud protocol offers a glimpse into users’ thought processes as they interact with a system. Participant utterances can reveal mismatches between their expectations and the system’s outcomes, shedding some light on their underlying mental models. This approach,

favored by Jakob Nielsen, involves a moderator periodically prompting users to verbalize their thoughts and expectations during a usability test. Across multiple participant sessions, recurring themes in user mental models often emerge.

Another method, promoted by Nikki Anderson-Stanier, is the

retrospective interview. Here, users are asked to recall past experiences and describe their thought processes, pain points, expectations, and goals. This method is particularly useful for scenarios where stimuli are unavailable, or for multi-channel experiences that might be difficult to replicate in a usability test.

You can also pose

a series of “what-if” questions to participants.

Stephen Payne’s research on ATMs used this approach, asking participants to predict outcomes based on various inputs. Through these questions, he discovered that participants varied widely in their beliefs about the information stored on debit cards.

Pairwise comparisons for

relatedness ratings involve documenting all the possible inputs and outputs and having participants rate the closeness of each pair on a scale. If you were measuring mental models of Photoshop, for example, you might include concepts like “layer,” “blur,” “smudge,” and so on. As the list of concepts grows, you run the risk of fatiguing participants. For 5 items, they only need to make 10 comparisons — but for 15 items, that grows to 105! The final output is a matrix showing the relative strength of each pairing.

Card sorting offers a different perspective by grouping items based on similarity, making it suitable for scenarios where distinct categories are expected. For a complex system with many elements, this simplifies data collection by giving participants a more manageable task.

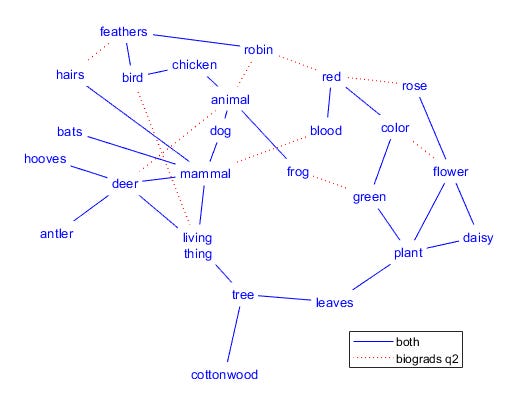

Pathfinder networks may be useful for analysis and visualization. This approach mathematically prunes away weakly related ideas, highlighting the essential. The resulting figure makes it easy to compare the mental models of different user groups. This approach also offers similarity and reliability statistics if you want to understand change over time. But be aware that while

analysis tools are freely available, they are no longer supported, posing potential challenges for researchers.

Read more…